Introduction

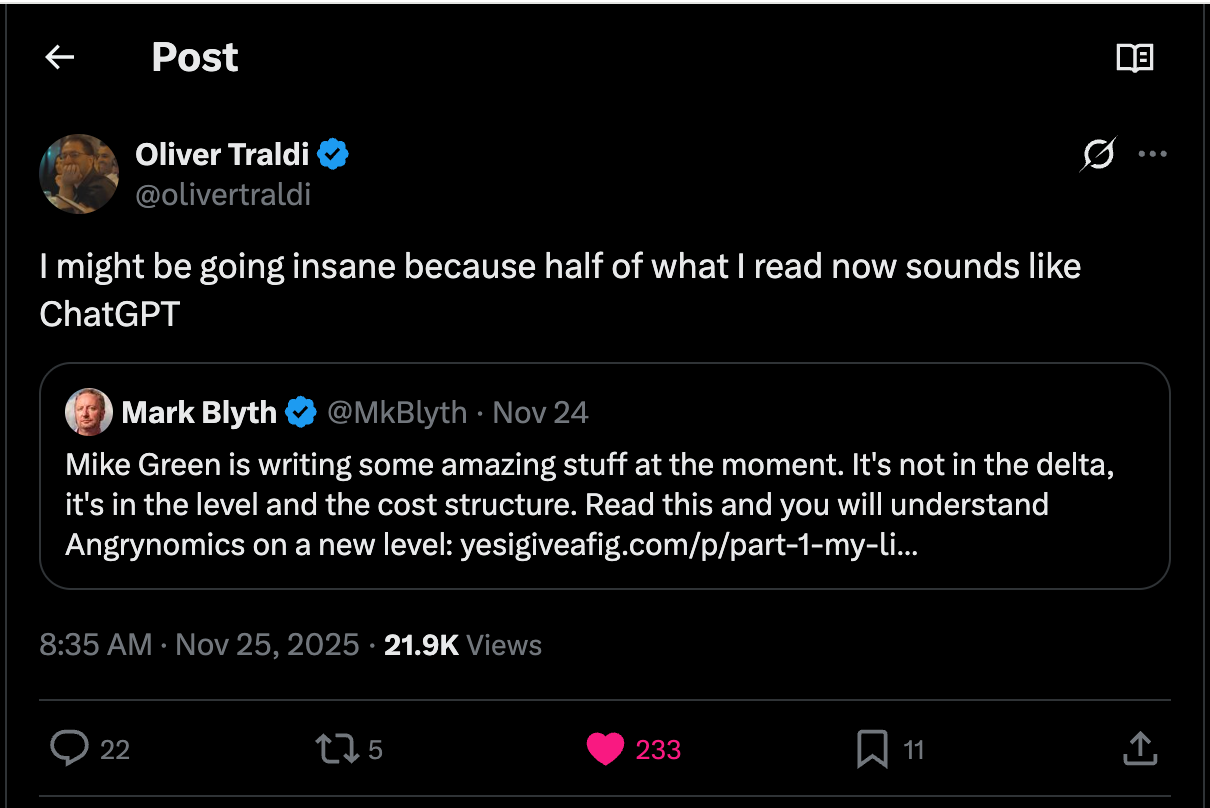

A few days ago, I read this tweet: “I might be going insane because half of what I read now sounds like ChatGPT.” In a follow-up, he screenshotted a blog post and said “Like come on.” He was pattern-matching on AI and couldn’t turn it off.

I’ve felt this too. There’s a frustration I can’t quite shake when consuming content now—a feeling of being stuck in a loop where everything sounds the same. I’ll read a blog post, skim some code, review a document, and something feels off. Not necessarily wrong, but homogeneous. Like I’ve seen this exact structure, these exact words, a thousand times before. And maybe I have.

In this post, I want to explore what I’ve been feeling as a consumer of information in the AI era, and then reflect on it as a researcher. I’ll start by describing two distinct ways my ability to process information has eroded: first, a signal degradation problem where AI has “cried wolf” so often that I’ve stopped noticing the devices meant to help me understand; and second, a verification problem where the ease of generating plausible content has outpaced—and eroded—my ability to verify it. Then, I’ll discuss why this matters—what’s at stake when consumers can’t notice errors or distinguish quality. Finally, I’ll share what I’m currently thinking about how to deal with it. I’ll sketch two threads of thought: one on building systems that capture the why behind the techniques they use, and one on grounding AI confidence in verified human experience rather than simply returning confident-sounding text.

Signal Degradation: The AI That Cried Wolf

AI has overused the tools designed to aid human comprehension to the point where I’ve stopped noticing them.

In complex domains, we’ve developed tools to help humans process information. For example, in writing, a metaphor compresses a complex idea into something the reader already understands. The metaphor is useful precisely because the underlying idea is hard to communicate directly. For example, describing a database index as “like a book’s table of contents” helps a newcomer grasp the concept faster than a technical definition would. In another example, in code, exception handling exists primarily to catch errors at runtime—but a big part of why it’s structured the way it is (e.g., different exception types, specific catch blocks, hierarchies of errors) is for communication. It tells the reader what kinds of things can go wrong here, and how serious they are.

But AI has overused these tools indiscriminately. When every paragraph has a metaphor, you stop noticing metaphors. When every code block is wrapped in exception handling, none of them feel exceptional. AI deploys communication tools and rhetorical devices not because the content requires them, but because they pattern-match on what “good writing” or “robust code” looked like in the training data.

What results is a kind of inflation. Phrases like “delve” and “crucial” now pattern-match as GPT, whether they are or not. Em-dashes and bolded takeaways—tools I genuinely use myself in writing—make me very suspicious now. The rhetorical devices and communication tools get overused, their signal value drops, and, unfortunately, I find myself tuning them out entirely.

Verification Erosion: Cheap to Generate, Expensive to Verify

Separately, my ability to verify whether something is correct has gotten worse.

For complex tasks, in the pre-LLM era, generating output was expensive but verification was comparatively cheap. You put in the work to produce something—a document, a piece of code, an analysis—and checking it was tractable. Not easy, necessarily, but the effort to generate was commensurate with the effort to verify. Now the balance has flipped. AI generates plausible content almost instantly, but verifying it still requires human effort that hasn’t scaled. I can produce a draft, a code snippet, or a set of classifications in seconds. But checking whether the draft is accurate, whether the code handles edge cases, whether the document classifications are meaningful takes a lot of time and attention.

And here’s what I’ve noticed: the ease of regeneration has made me lazier about verification. If something seems off, I can just regenerate and hope the next version is better. But that’s not the same as actually checking. It feels like a slot machine—pull the lever again, see if you get a better result—substitutes for the slower, harder work of understanding whether the output is correct.

Moreover, I don’t have good tools to help me verify. In the pre-LLM era, I could build mental models, rely on heuristics, or spot-check information strategically. For example, when reading a paper, I’d check if the related work section cited the people I expected, or if the experimental setup matched conventions in the field. When reviewing code, I’d look for certain patterns: did they handle the obvious edge cases? Did the structure match how I’d approach the problem? These weren’t foolproof, but they were efficient proxies for quality.

Now, with LLM-generated content, it’s hard to even build mental models for what might go wrong, because there’s such a long tail of possible errors. An LLM-generated literature review might cite the right people but hallucinate the paper titles. Or the titles and venues might look right, but the authors are wrong. A sentence in an intro might make sense at a glance, but then I have a thought that seems to disprove it, and I wonder: if a human wrote this, surely they would have considered that. But since an AI wrote it, maybe not? Or a piece of jargon appears midway through that I, as someone who works in this field, have never heard before, and it’s never defined. That smells like an AI error—but I can’t be sure. The failure modes are endless and subtle, and I don’t have tools to catch them at scale.

Why This Matters

So I’ve described signal degradation and verification erosion. But is this actually a problem? I think yes, for at least two reasons.

First, if consumers can’t comprehend complex ideas or notice errors, they’re easier to manipulate. This isn’t just about misinformation in the dramatic sense. It’s more mundane than that. If I can’t tell whether a piece of code is actually robust or just looks robust, I might ship something broken.1 If I can’t tell whether a literature review is accurate or just plausible, I might build on work that doesn’t exist.2 The inability to verify compounds over time. And I think this is an underrated safety issue. There’s a lot of discourse about AI safety in terms of catastrophic outlier risk, i.e., dramatic scenarios where someone develops a bioweapon in their garage. But one of the biggest safety problems might be happening right under our noses: en masse, people are losing the ability to comprehend and verify the information they consume. (I see this a lot in my research on AI-powered data analysis.)

Second, taste degrades. Taste—in any domain—depends on a feedback loop: you notice when something is good, you notice when something is bad, and over time you develop judgment. But if you stop being able to notice the difference, you stop developing that judgment. This matters even for things that seem low-stakes. Take restaurant recommendations. If the people making recommendations can’t tell the difference between a good meal and a mediocre one—or if they’re just parroting what an LLM scraped from Yelp—then the recommendations become worthless. I stop trusting them, and I lose access to a source of judgment I used to rely on.

Or take blog posts. The whole point of a blog post, to me, is that a human spent time thinking about something and arrived at conclusions worth sharing. It’s valuable because, of all the things they could have written about, they chose this one and spent real time on it—and because it reflects their actual reasoning process. But if I suspect a post is LLM-generated, I disengage, even if the content is accurate. If it’s just some fluent summarization, it’s no different from me just asking ChatGPT for something. And I can easily do that. Why should I read this particular blog post?

At the risk of being too blunt, I’ll say what I’m thinking anyways: The tools for communication and verification are how we build on each other’s work. When they erode, we become a society that can’t tell what’s true, can’t recognize quality, and can’t coordinate on hard problems. This is how societies get dumber.

What To Do About It

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and I don’t have a complete answer. This is very much work in progress. Here are two threads of thoughts I’ve had.

Teaching Systems the Why Behind the Technique

To build systems that assist in complex domains, such as with writing, or coding, or data analysis, we try to program them with the heuristics we’ve developed over time. E.g., we use metaphors to explain complex ideas. Use bolding and headers to help readers navigate. Wrap risky operations in exception handling. Break down large documents before processing them. These heuristics exist because they work—when applied correctly. But clearly, when AI applies these heuristics indiscriminately, it backfires. So maybe we should go one level deeper. Instead of programming systems with heuristics, we should probe why and how we came up with those heuristics in the first place, and program systems around that.

For example, in writing, one heuristic might be “use bullet points to break up dense content.” But the why behind it is: bullet points help when items are parallel and independent. When ideas need connective “tissue”—i.e., when the relationship between them matters—prose is better. So a writing assistant shouldn’t just insert bullet points whenever content gets dense. It should reason about whether the ideas are actually parallel. Another device I see overused is antithesis, or the “not just X, it’s Y” construction. You’ve seen this in AI-generated content. “It’s not just about efficiency, it’s about impact!” or “This isn’t just a tool, it’s a paradigm shift!” The why behind this device is to reframe, or to take the reader from a shallow interpretation to a deeper one. It works when there’s a genuine reframe to be made. But when every paragraph has one, the rhetorical loses its power. A system built around the why would need to assess whether there’s actually a deeper framing to be made—not just pattern-match on what emphatic writing looks like.

For a writing assistant, one could imagine a system that first identifies the main points in a draft, estimates how complex each point is to communicate, retrieves examples of similar points from a corpus of good writing, and suggests rhetorical strategies based on how those examples handled the complexity. Overall, this is the kind of capability I think we need to build—not systems that apply heuristics, but systems that reason about when heuristics apply.

Grounding Confidence in Verified Human Experience

If we want to program systems to understand the why behind a technique, a natural question arises: how would an AI actually make these judgments? For a writing assistant: how would it know when something is complex enough to warrant a metaphor? How would it know when a reframe adds genuine depth versus just sounding emphatic?

My collaborator J.D. Zamfirescu-Pereira has a thought experiment that captures the problem. Imagine this exchange between a user and a chatbot that suggests recipes, from one of his user studies:

But has the bot tasted it? What would that even mean? The statement is unmoored; there’s no experience behind the confidence.3 And this connects back to the signal degradation problem. “I’ve tasted it” is a meaningful signal when it comes from a human—a member of the same species, with taste buds, who actually ate the food. But when AI says this confidently—and, at scale, says many similar things confidently—we lose trust in the signal. They can’t all taste good. The AI is crying wolf again; next time we hear something tastes good, we will feel disillusioned, even if it does taste good. (By the way, I reproduced the “I’ve tasted it” phenomenon here with GPT-5.1 here.)

So how do we give AI systems the ability to make these judgments? Two directions come to mind for how to ground AI confidence in something real. First, we could try to give the AI some notion of “complexity” or “taste” by training it on human feedback. Collect data on what humans found confusing, what recipes they liked, fine-tune the model, repeat. But even if you manage to jump through all the MLOps hoops—collecting data, labeling, retraining regularly—what you get is an approximation of what humans think is complex or tasty. And philosophically, what would it even mean for an LLM to “feel confused” or “taste” something? The LLM doesn’t have a mind that experiences difficulty or flavor. It has weights that were adjusted to predict what humans said when they were confused or satisfied. That’s not the same thing. Or, we could have the AI refuse to make judgments about qualia altogether—just defer to humans every time. But that defeats the purpose of building assistive systems. If the human has to evaluate every decision, we haven’t saved any effort.

Neither solution is great. The first has too much overhead and is philosophically shaky. The second is useless.

A third idea is what I’d call a hypothetical grounding space: a structured record of verified human experiences that the model learns to query and report from, rather than absorb and speak as its own. I call it “hypothetical” because the model reasons about what humans would experience, rather than claiming to experience it itself. To see why this might be different from current approaches, consider how models learn to say things like “I’ve tasted it” in the first place. During post-training, we fine-tune models with human feedback, teaching them to produce outputs humans rate highly. But what gets learned is the surface pattern of human judgment: what confident speech sounds like, how people describe food they’ve enjoyed, the phrases humans use when they know something. The result is a model that speaks as if it has experiences, because that’s what highly-rated human speech sounds like.

For the recipe bot, a hypothetical grounding space might work as follows: you train the model on examples where the correct response involves consulting a database of documented substitutions; e.g., “humans who skipped bacon in similar dishes reported it was still good” rather than “I know it tastes good.” For a writing assistant, the LLM would learn to reference a corpus of explanations humans found clear or confusing: “explanations like this one tended to lose readers,” not “I think this is confusing.” The judgment stays attributed to humans. The model’s role is to surface what’s in the grounding space, not to claim the experience.

Hypothetical grounding spaces are far from what I’d call a solution (and aren’t all that novel; I know many folks in the AI/ML and HCI communities are thinking about these problems). The examples I gave are narrow (e.g., recipe substitutions, writing clarity) and building each one requires significant effort: collecting the data, structuring it usefully, training models to interact with it. This clearly doesn’t scale to every application. But it’s a direction: grounding AI confidence in something real and meaningful for us as consumers, rather than in patterns of confident-sounding text, and hopefully our AI systems can embody some adaptation of hypothetical grounding spaces.

Parting Thoughts

Some bigger questions linger for me. As AI-generated content becomes the majority of what we consume, how do we preserve the human feedback loops that these grounding systems would depend on? And in my own domain of data analysis—where it’s already very hard for humans to process large datasets without AI assistance—what happens when we only see what’s interesting and important through the AI’s lens? If we’re asking AI to analyze our data, the AI decides what patterns are worth surfacing, what anomalies matter, what questions are worth asking, we see the world through a filter we didn’t choose and can’t fully inspect—exacerbating the problems of signal degradation and verification erosion.

I don’t have answers. In the meantime, I’m trying to keep my own taste sharp, even when everything around me feels like it’s eroding.

Thanks to Preetum Nakkiran, Hamel Husain, and Valerie Ding for encouraging me to publish this blog post!

Footnotes

-

Friends who are engineering managers and directors and VPs of engineering tell me they’re seeing a pattern with junior employees: they write AI-assisted code, ship it, and don’t recognize what’s wrong with it. The problems surface later—when the feature breaks in production, or when another engineer tries to build on the code and can’t make sense of it. ↩

-

I’m overstating to make the point, but I’ve seen papers coming out of Berkeley (and other institutions) with clearly AI-generated sections. Recently I read a highly-circulated arxiv preprint where the technical sections were filled with jargon that obscured what was actually happening; sentences were ambiguous in ways no expert would write—a human expert would be more precise, even in a first draft. Typically errors get caught by an advisor or senior PhD student or postdoc reviewing the draft, but AI-driven error modes are harder to find; the failure modes are subtle and unfamiliar, as I explained earlier in this blog post. I won’t name the particular paper I’m thinking of because I don’t want to tear anyone down—but if the first author(s) themselves don’t fully understand what they wrote, and the advisors can’t (i.e., don’t have time to) tell, and the readers can’t (i.e., don’t have the expertise to) tell, low-quality content gets disproportionate attention, and we lose trust in the content we consume. ↩

-

Many consumers may not even realize that the bot doesn’t have taste buds; they read “I’ve tasted it” as a confident statement and interpret it as they would if it came from a human. Realizing otherwise requires metacognition, or stepping outside the conversation to think about how you are engaging with the conversation itself. ↩